-

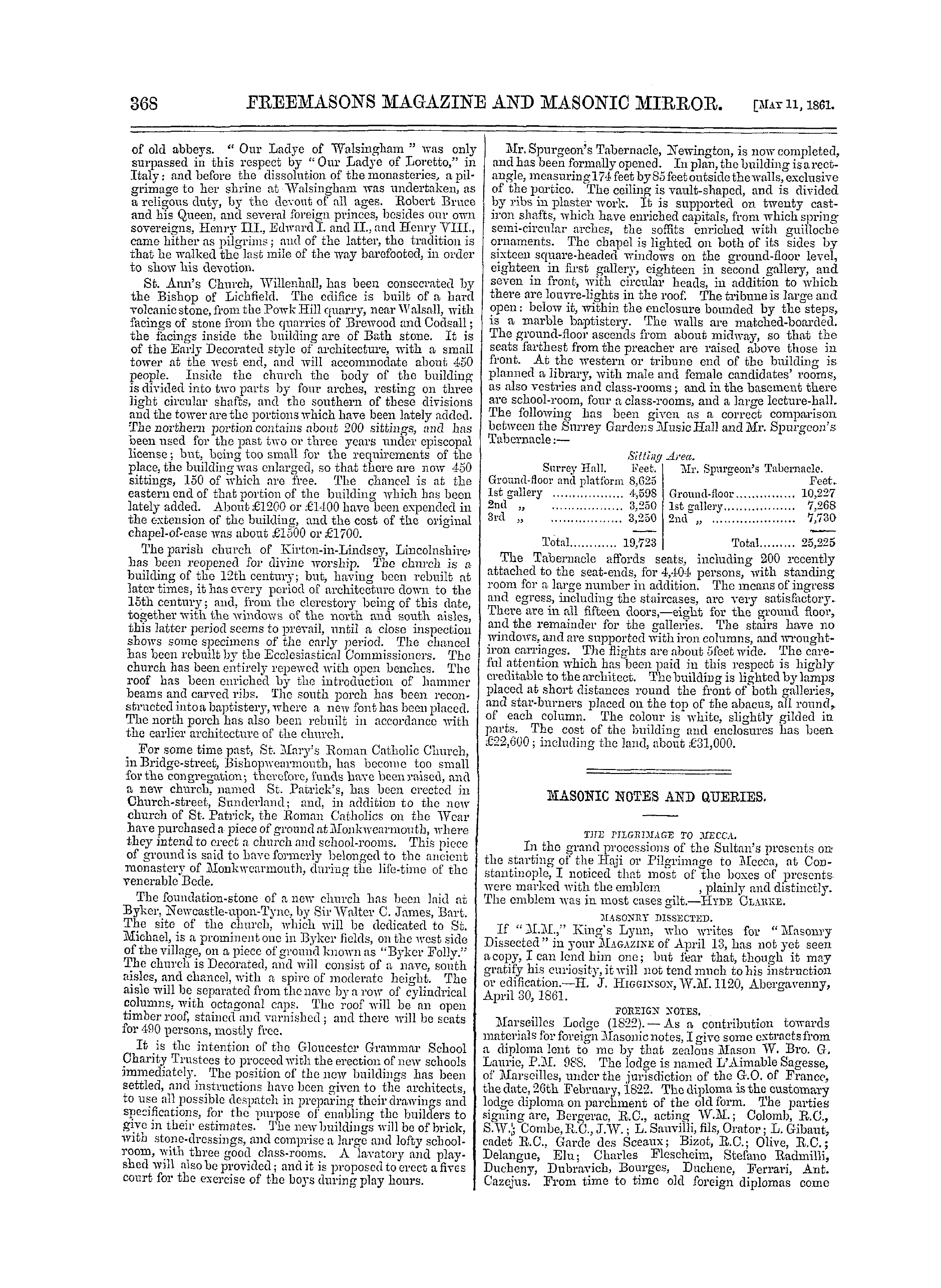

Articles/Ads

Article ARCHITECTURE AND ARCHÆOLOGY. ← Page 2 of 4 →

Note: This text has been automatically extracted via Optical Character Recognition (OCR) software.

Architecture And Archæology.

practice , we could hardly have believed that such a people as the Greeks would have so wrought . However , as my audience are not perhaps conversant with Quatremere de Quincy's or Midler's account of these proceedings , I will give a few sentences on the subject drawn from what they say . First , I would premise that these Cruseo-elephantiue , or gold aud ivory statues , were not uncommon in Greece and

the Grecian Islands , and iudeed that it was a received way of making a god in those days , and that moreover they wero not unf ' requentiy of great size . TheJupiter of Elis , although seated , was sixty feet high ; and the Minerva of the Parthenon , standing , forty feet . Both of those were by Phidias . Among various other large examples of this art were the Juuo of Argosby- Polycletus ; the Esculapius at Eidaurus

, p , by Thasymedes ; and the " Great Goddesses , " at Megalopolis , by Damaphoon . The first thing to bo clone in making these giant works , after the model was prepared , was to put together a great framework of wood as a core , 3-ct hollow within so that the workmen could get inside to adjust the work and rivet the veneers of ivory ancl gold which were to form the surface ;

ancl no doubt , for convenience , they had stages and staircases within these great statues , the wooden framework of which was , as Muller informs us , strengthened across with rods of metal . But he shall speak for himself . In division 312 of his elaborate work on ancient art , this author thus informs us : — "The ancients received from India , but especially from Africaelephant's teeth of considerable sizebthe litting

, , y sp and bending of which , ' a lost art-, ' but one of which certainly existed in antiquity , they could obtain plates of ivory from 12 to 20 iii . in breadth . " I may here be allowed to remark that in the Exhibition of 18-51 , this "lost art , " so called by Muller , semed to have been , revived and carried even further than by the Greeks . A prize medal on that

occasion was awarded to Messrs . J . Pratt and Co ., Merdan , Connecticut , United States , for specimens of ivory veneers cut by machinery . "These veneers wore exceedingly delicate "—I am quoting the official report—" one piece alone being 12 iu . iu breadth , and 1-Oiii . in length , and having been sawn from a single tusk . Perhaps sonic of those present may remember this remarkable example of the

ingenuity of our brothers over the water , pendant spirally , like a great carpenter ' s shaving . But to return to these great Greek statues . " In cxecn ting one of these , " says Midler , " after the surface of the model ivas distributed in such a ivay as could best be reproduced in these plates , the individual portions were accurately represented by sawing , planing , and filing the ivory , and afterwards joined together ,

especially by tlicusc 01 isinglass , over a kernel of wood and metal rods . " "The holding together-, however" ' , he adds , " ofthe pieces required incessant- care , " as indeed we may well conceive , as ivory is apt to expand and contract , and warp , and cur ] , in changes of moisture and temperature . Indeed it must bo acknowledged that the ivhole process and sham nature of the work thus described , impresses us with want of dignity , lack of permanence , and thc necessity of repair .

Prom a passage 111 Valerius Maxiuius , it appears that Phidias desired to make this figure of Minerva , for the Parthenon , not after this fashion , but in marble , but he ivas overruled . Had the sculptor had his way , we should probably have had now existing some grand aud noble remains of it-, in addition to those invaluable fragments of some of the subordinate statues which wc possess in the British

Museum . But the priests had their way . Idolatry had its way instead of art , aud in consequence—oh , just retribution ! —not a pinch of dust remains of their Daughter of Jove . Now , t-adcris paribus , the priests must , ive may suppose , have desired permanence for their god , aud must have been well aware that this upholstery manufacture mode of making it was not likely to last liko marble . Also , this mode could

not have becu . selected , as has been suggested , merely becauso of its superior costliness , because the introduction to a greater degree of gems with thc gold , as wars sometimes done , would easily have made thc marble Jwork as costly as , or more so , than the ivory . Also , tho untouched surface of ivory is by no means more beautiful as a representation of flesh than marble , much less so indeed as regards permanence , as it gets yellow and discoloured . Butthen , on the other hand , it is hishlv suitable for i-eceiviu _ r the most

delicate and pure tints . It is , therefore , much used by miniature painters . Most of the beautiful works exhibited last year iu this room , of the late Sir 'William floss , were painted on this material . It is probable , however , that the ivory surfaces of these colossal statues were rather stained than paiuted ; and ivory takes these stains eveuly and with facility , which marble does not . The examples , indeed ,

which I have seen of colouring marble , especially with tinted wax , have been singularly unfortunate . Marble is apt to be unequal in its grain , and takes the colouring matter capriciously . In the imitation of flesh , a greasy , unpleasant effect is the result , and where the grain of the marble shows coarsely , what is vulgarly called a" a goose flesh" appearance is produced , which is certainly ' neither agreeable nor divine .

Doubtless the Greeks imagined that their gods had pure complexions as well as beautiful features . The empyrean airs of heaven might well be supposed to imbue these with an exquisite delicacy not to be imitated by the permanent treatment of any surface less capable of refined tints than ivory . I am well aware that in the few last sentences I have been hazarding a somewhat novel theory , in this special

reason I have submitted for the use of ivory iu the colossal idol art of the Greeks , but pray accept that I do not do this dogmatically , but only for discussion . Even , however , in entertaining this view of these great statues of the presiding genii of the Greek temples having been thus surfaced with ivory for the purpose of being coloured up to a refined version of the tints of naturewe

, must not be under the impression that they had a common , vulgar effect , like that of wax figures , for which we have an instinctive repugnance . This , indeed , would have defeated the very object which the priests had in view , that of impressing the multitude . Indeed , in as far as it could work at such a disadvantage , no doubt the exquisite taste of the Greeks was also applied to the finish of these works . The

Minerva of the Parthenon was 110 mere sham of a great woman , but iu the hands of Phidias ivas a bold , though a coerced attempt to realise tho tutelar divinity of Athens , the immortal Virgin of Wisdom—a being solemn aud impassive , far above the human level , aud through ivhose veins course , not blood , but celestial ichor . Dramatic effect iu their worshiwas ever ht bthe

p soug y Greeks , and it was only at special times that their divinities ivere unveiled at all to the general people . On such occasions every means was taken to work upon the senses . Coloured curtains tinted the light , ceremony lent its impression , aud

music and thc chant their charm . Censers filled the air with their ambrosial stream , and sacrificial clouds waved before the divinity , like those of his own imaginary heaven , from behind which , to thc entranced votary , well might the mystic god almost or quite seem to breathe , frown , or smile . This was " a consummation devoutly to be wished " by the priests , for then tho fame of their god increased , and

offerings flowed into their treasury . To effect impressions like these , doubtless was it that these great statues were painted up to a key of divine life , ivhieh assuredly could not have been reached by the more natural tints of ivory and gold .. It was to accomplish this that tho powers of such as Phidias were thus coerced , and it was under all these devices that these magnificent idols were manufactured in

those old days as the agents of polytheism and superstition . Whenever , also , the statue of the god himself , in the penetralia of his own marble house , was thus treated with the hues of life , doubtless its own immediate subordinates around , especially within the building , had in some degree to wear his livery . Also when polychromy spread in addition over thc exterior architectureharmony dictated

, that some variation of colour should lie connected also with the outside sculpture , as especially in the backgrounds of the tympana , metopes , aud friezes . " As regards , however , the statues themselves in these situations , the variety of tint was probably confined to that obtained hy difference of material , as iu shields , swords , helmets , and bridles of metaland not badded surface colour requiring constant

, y and extensive repairs not capable of being done " in secret , as was thc case with the interior figures . Thus do I conceive that thc Greeks did colour some of their statues , and that they did so in different decrees ,

Note: This text has been automatically extracted via Optical Character Recognition (OCR) software.

Architecture And Archæology.

practice , we could hardly have believed that such a people as the Greeks would have so wrought . However , as my audience are not perhaps conversant with Quatremere de Quincy's or Midler's account of these proceedings , I will give a few sentences on the subject drawn from what they say . First , I would premise that these Cruseo-elephantiue , or gold aud ivory statues , were not uncommon in Greece and

the Grecian Islands , and iudeed that it was a received way of making a god in those days , and that moreover they wero not unf ' requentiy of great size . TheJupiter of Elis , although seated , was sixty feet high ; and the Minerva of the Parthenon , standing , forty feet . Both of those were by Phidias . Among various other large examples of this art were the Juuo of Argosby- Polycletus ; the Esculapius at Eidaurus

, p , by Thasymedes ; and the " Great Goddesses , " at Megalopolis , by Damaphoon . The first thing to bo clone in making these giant works , after the model was prepared , was to put together a great framework of wood as a core , 3-ct hollow within so that the workmen could get inside to adjust the work and rivet the veneers of ivory ancl gold which were to form the surface ;

ancl no doubt , for convenience , they had stages and staircases within these great statues , the wooden framework of which was , as Muller informs us , strengthened across with rods of metal . But he shall speak for himself . In division 312 of his elaborate work on ancient art , this author thus informs us : — "The ancients received from India , but especially from Africaelephant's teeth of considerable sizebthe litting

, , y sp and bending of which , ' a lost art-, ' but one of which certainly existed in antiquity , they could obtain plates of ivory from 12 to 20 iii . in breadth . " I may here be allowed to remark that in the Exhibition of 18-51 , this "lost art , " so called by Muller , semed to have been , revived and carried even further than by the Greeks . A prize medal on that

occasion was awarded to Messrs . J . Pratt and Co ., Merdan , Connecticut , United States , for specimens of ivory veneers cut by machinery . "These veneers wore exceedingly delicate "—I am quoting the official report—" one piece alone being 12 iu . iu breadth , and 1-Oiii . in length , and having been sawn from a single tusk . Perhaps sonic of those present may remember this remarkable example of the

ingenuity of our brothers over the water , pendant spirally , like a great carpenter ' s shaving . But to return to these great Greek statues . " In cxecn ting one of these , " says Midler , " after the surface of the model ivas distributed in such a ivay as could best be reproduced in these plates , the individual portions were accurately represented by sawing , planing , and filing the ivory , and afterwards joined together ,

especially by tlicusc 01 isinglass , over a kernel of wood and metal rods . " "The holding together-, however" ' , he adds , " ofthe pieces required incessant- care , " as indeed we may well conceive , as ivory is apt to expand and contract , and warp , and cur ] , in changes of moisture and temperature . Indeed it must bo acknowledged that the ivhole process and sham nature of the work thus described , impresses us with want of dignity , lack of permanence , and thc necessity of repair .

Prom a passage 111 Valerius Maxiuius , it appears that Phidias desired to make this figure of Minerva , for the Parthenon , not after this fashion , but in marble , but he ivas overruled . Had the sculptor had his way , we should probably have had now existing some grand aud noble remains of it-, in addition to those invaluable fragments of some of the subordinate statues which wc possess in the British

Museum . But the priests had their way . Idolatry had its way instead of art , aud in consequence—oh , just retribution ! —not a pinch of dust remains of their Daughter of Jove . Now , t-adcris paribus , the priests must , ive may suppose , have desired permanence for their god , aud must have been well aware that this upholstery manufacture mode of making it was not likely to last liko marble . Also , this mode could

not have becu . selected , as has been suggested , merely becauso of its superior costliness , because the introduction to a greater degree of gems with thc gold , as wars sometimes done , would easily have made thc marble Jwork as costly as , or more so , than the ivory . Also , tho untouched surface of ivory is by no means more beautiful as a representation of flesh than marble , much less so indeed as regards permanence , as it gets yellow and discoloured . Butthen , on the other hand , it is hishlv suitable for i-eceiviu _ r the most

delicate and pure tints . It is , therefore , much used by miniature painters . Most of the beautiful works exhibited last year iu this room , of the late Sir 'William floss , were painted on this material . It is probable , however , that the ivory surfaces of these colossal statues were rather stained than paiuted ; and ivory takes these stains eveuly and with facility , which marble does not . The examples , indeed ,

which I have seen of colouring marble , especially with tinted wax , have been singularly unfortunate . Marble is apt to be unequal in its grain , and takes the colouring matter capriciously . In the imitation of flesh , a greasy , unpleasant effect is the result , and where the grain of the marble shows coarsely , what is vulgarly called a" a goose flesh" appearance is produced , which is certainly ' neither agreeable nor divine .

Doubtless the Greeks imagined that their gods had pure complexions as well as beautiful features . The empyrean airs of heaven might well be supposed to imbue these with an exquisite delicacy not to be imitated by the permanent treatment of any surface less capable of refined tints than ivory . I am well aware that in the few last sentences I have been hazarding a somewhat novel theory , in this special

reason I have submitted for the use of ivory iu the colossal idol art of the Greeks , but pray accept that I do not do this dogmatically , but only for discussion . Even , however , in entertaining this view of these great statues of the presiding genii of the Greek temples having been thus surfaced with ivory for the purpose of being coloured up to a refined version of the tints of naturewe

, must not be under the impression that they had a common , vulgar effect , like that of wax figures , for which we have an instinctive repugnance . This , indeed , would have defeated the very object which the priests had in view , that of impressing the multitude . Indeed , in as far as it could work at such a disadvantage , no doubt the exquisite taste of the Greeks was also applied to the finish of these works . The

Minerva of the Parthenon was 110 mere sham of a great woman , but iu the hands of Phidias ivas a bold , though a coerced attempt to realise tho tutelar divinity of Athens , the immortal Virgin of Wisdom—a being solemn aud impassive , far above the human level , aud through ivhose veins course , not blood , but celestial ichor . Dramatic effect iu their worshiwas ever ht bthe

p soug y Greeks , and it was only at special times that their divinities ivere unveiled at all to the general people . On such occasions every means was taken to work upon the senses . Coloured curtains tinted the light , ceremony lent its impression , aud

music and thc chant their charm . Censers filled the air with their ambrosial stream , and sacrificial clouds waved before the divinity , like those of his own imaginary heaven , from behind which , to thc entranced votary , well might the mystic god almost or quite seem to breathe , frown , or smile . This was " a consummation devoutly to be wished " by the priests , for then tho fame of their god increased , and

offerings flowed into their treasury . To effect impressions like these , doubtless was it that these great statues were painted up to a key of divine life , ivhieh assuredly could not have been reached by the more natural tints of ivory and gold .. It was to accomplish this that tho powers of such as Phidias were thus coerced , and it was under all these devices that these magnificent idols were manufactured in

those old days as the agents of polytheism and superstition . Whenever , also , the statue of the god himself , in the penetralia of his own marble house , was thus treated with the hues of life , doubtless its own immediate subordinates around , especially within the building , had in some degree to wear his livery . Also when polychromy spread in addition over thc exterior architectureharmony dictated

, that some variation of colour should lie connected also with the outside sculpture , as especially in the backgrounds of the tympana , metopes , aud friezes . " As regards , however , the statues themselves in these situations , the variety of tint was probably confined to that obtained hy difference of material , as iu shields , swords , helmets , and bridles of metaland not badded surface colour requiring constant

, y and extensive repairs not capable of being done " in secret , as was thc case with the interior figures . Thus do I conceive that thc Greeks did colour some of their statues , and that they did so in different decrees ,