-

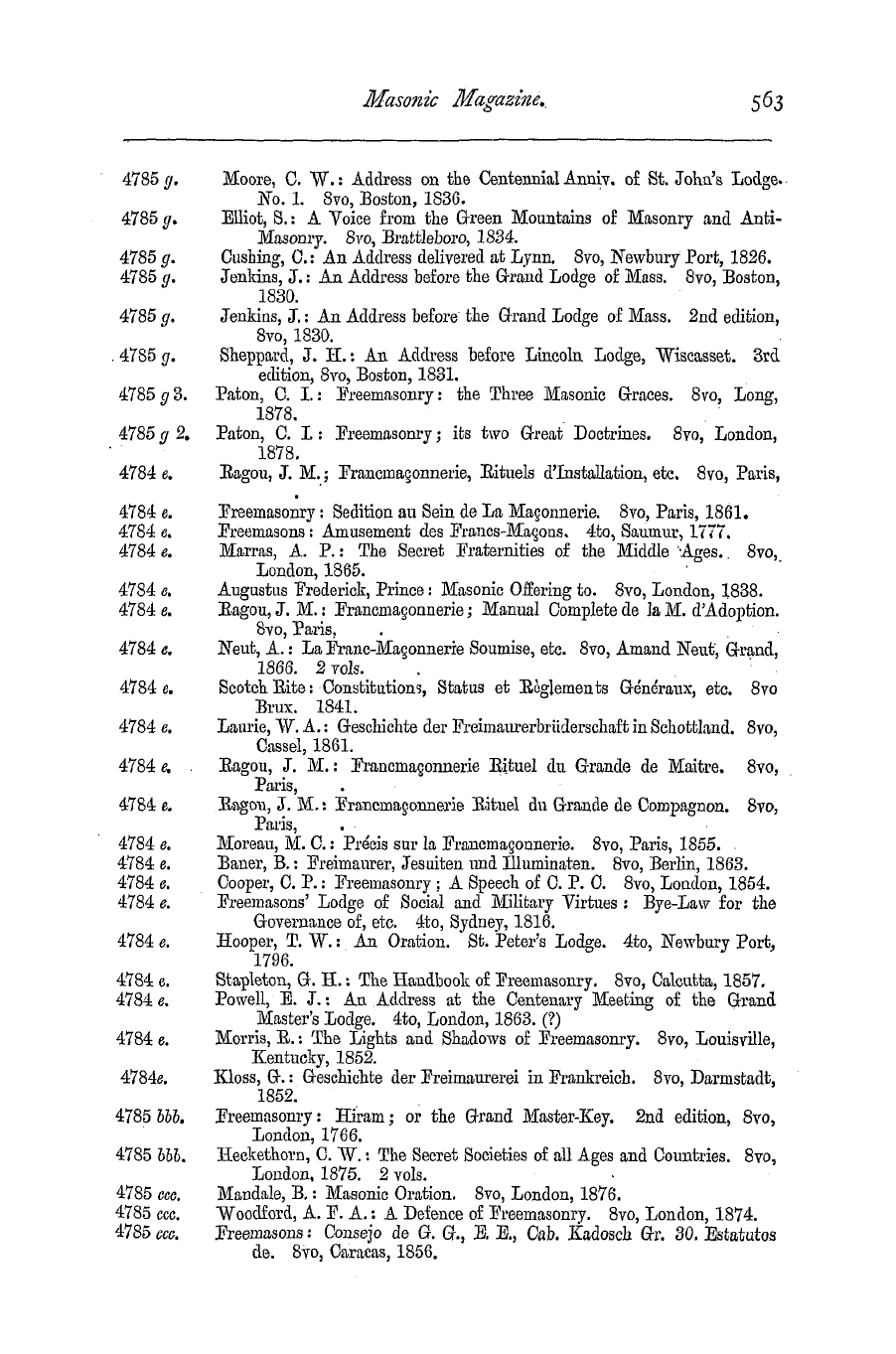

Articles/Ads

Article CATHERINE CARMICHAEL; on, THREE YEARS RUNNING. ← Page 5 of 15 →

Note: This text has been automatically extracted via Optical Character Recognition (OCR) software.

Catherine Carmichael; On, Three Years Running.

there was no question but that it had been belter and more plentiful at the diggings . For the food she would not have cared at all , —but she did care for the way in which it was doled out to her hands , so that at every dole she came fo hate him more . The meat was plentiful enough . . The men who took their rations from the station came there and cut it from the sheep as they were slaughtered , almost as they would . Peter would count the sheep ' s heads every week , and would then know that , within a certain wide margin , he had not been robbed . Could she have made herself happy with mutton she might have

lived a blessed life . But of other provisions every ounce was weighed to her , as it was to the station hands . So much tea for the week , so much sugar , so much flour , and so much salt . That was all , —unless when he was tempted to buy a sack of potatoes by some itinerant vendor , when he would count them out almost one by one . There was a storeroom attached fo the kitchen , double-locked , the strongest of all the buildings about the place . Of this , for some month or two , he never allowed her to see the inside . She became aware that there were other delicacies there besides the tea and sugar , —jam ancl pickles , and boxes of sardines . The station-hands about the place , as the shepherds

were called , would come and take the pots and bottles away with them , and Peter would score them down in his book and charge them in his account of wages against the men , with a broad profit to himself . But there could be no profit in sending such luxuries into the house . And then , as the ways of these people became gradually known to her , she learned that the rations which had been originally allowedfor Peter himself and the old woman and the Maori had never been increased at her coining . Bations for three were made to do as rations for four . " It's along of that he ' s a-starving of

you us , " said the old woman . Why on earth should he have married her and brought her there , seeing that there was so little need for her ! But he had known what he was about . Little though she found for her to do , there was something which added to his comfort . She could cook , —an art which the old woman did not possess . She could mend his clothes , and it was something for him to have some one to speak to him . Perhaps in this way he liked herthough it was as a

, man may like a dog whom he licks into obedience . Though he would tell her that she was sulky , and treat her with rough violence if she answered him , yet he never repented him of his bargain . If there was work which she could do , he took care not to spare her , —as when the man came for the sheepskins , and she had to hand them out across the verandah , counting them as she did so . But there was , in truth , little for her to do .

There was so little to do , that the hours and days crept by with feet so slow that they never seemed to pass away . And was it to be thus with her for always , —for her , with her young life , and her strong hands , and her thoughts always full ? Could there be no other life than this ? And if not , could there be no death ? And then she came to hate him worse and worse , —to hate him and despise him , telling herself that of all human beings he was the meanest . Those miners who would work for weeks among

the clay , —working almost day and night , —with no thought but of gold , and who then , when gold had been found , would make beasts of themselves till the gold was gone , were so much better than him ! Better 1 why , they were human ; while this wretch , this husband of hers , was meaner than a crawling worm ! When she had been married to him about ei ght months , it was with difficulty that she could prevail upon herself not toted him that she hated him .

The only creature about the place that she could like was the Maori . He was silent , docile , and uncomplaining . His chief occupation was that of drawing water andhewing wood . If there was aught else to do , he would be called upon to do it , ancl in his slow manner he would set about the task . About twice a month he would go to thenearest post-office , which was twenty miles off , and take a letter , or , perhaps , fetch one . The old woman and the squatter would abuse him for everything or nothing ; and the Maori , to speak the truth , seemed to care little for what they said . But Catherine was kind to him , and he liked her kindness . Then there fell upon the squatter a sense of jealousy , —or feeling , probably , that his wife ' s words were softer to the Maori than to himself , —and the Mao ' ri was dismissed . "What s that for ? " asked Catherine sulkily-

Note: This text has been automatically extracted via Optical Character Recognition (OCR) software.

Catherine Carmichael; On, Three Years Running.

there was no question but that it had been belter and more plentiful at the diggings . For the food she would not have cared at all , —but she did care for the way in which it was doled out to her hands , so that at every dole she came fo hate him more . The meat was plentiful enough . . The men who took their rations from the station came there and cut it from the sheep as they were slaughtered , almost as they would . Peter would count the sheep ' s heads every week , and would then know that , within a certain wide margin , he had not been robbed . Could she have made herself happy with mutton she might have

lived a blessed life . But of other provisions every ounce was weighed to her , as it was to the station hands . So much tea for the week , so much sugar , so much flour , and so much salt . That was all , —unless when he was tempted to buy a sack of potatoes by some itinerant vendor , when he would count them out almost one by one . There was a storeroom attached fo the kitchen , double-locked , the strongest of all the buildings about the place . Of this , for some month or two , he never allowed her to see the inside . She became aware that there were other delicacies there besides the tea and sugar , —jam ancl pickles , and boxes of sardines . The station-hands about the place , as the shepherds

were called , would come and take the pots and bottles away with them , and Peter would score them down in his book and charge them in his account of wages against the men , with a broad profit to himself . But there could be no profit in sending such luxuries into the house . And then , as the ways of these people became gradually known to her , she learned that the rations which had been originally allowedfor Peter himself and the old woman and the Maori had never been increased at her coining . Bations for three were made to do as rations for four . " It's along of that he ' s a-starving of

you us , " said the old woman . Why on earth should he have married her and brought her there , seeing that there was so little need for her ! But he had known what he was about . Little though she found for her to do , there was something which added to his comfort . She could cook , —an art which the old woman did not possess . She could mend his clothes , and it was something for him to have some one to speak to him . Perhaps in this way he liked herthough it was as a

, man may like a dog whom he licks into obedience . Though he would tell her that she was sulky , and treat her with rough violence if she answered him , yet he never repented him of his bargain . If there was work which she could do , he took care not to spare her , —as when the man came for the sheepskins , and she had to hand them out across the verandah , counting them as she did so . But there was , in truth , little for her to do .

There was so little to do , that the hours and days crept by with feet so slow that they never seemed to pass away . And was it to be thus with her for always , —for her , with her young life , and her strong hands , and her thoughts always full ? Could there be no other life than this ? And if not , could there be no death ? And then she came to hate him worse and worse , —to hate him and despise him , telling herself that of all human beings he was the meanest . Those miners who would work for weeks among

the clay , —working almost day and night , —with no thought but of gold , and who then , when gold had been found , would make beasts of themselves till the gold was gone , were so much better than him ! Better 1 why , they were human ; while this wretch , this husband of hers , was meaner than a crawling worm ! When she had been married to him about ei ght months , it was with difficulty that she could prevail upon herself not toted him that she hated him .

The only creature about the place that she could like was the Maori . He was silent , docile , and uncomplaining . His chief occupation was that of drawing water andhewing wood . If there was aught else to do , he would be called upon to do it , ancl in his slow manner he would set about the task . About twice a month he would go to thenearest post-office , which was twenty miles off , and take a letter , or , perhaps , fetch one . The old woman and the squatter would abuse him for everything or nothing ; and the Maori , to speak the truth , seemed to care little for what they said . But Catherine was kind to him , and he liked her kindness . Then there fell upon the squatter a sense of jealousy , —or feeling , probably , that his wife ' s words were softer to the Maori than to himself , —and the Mao ' ri was dismissed . "What s that for ? " asked Catherine sulkily-