-

Articles/Ads

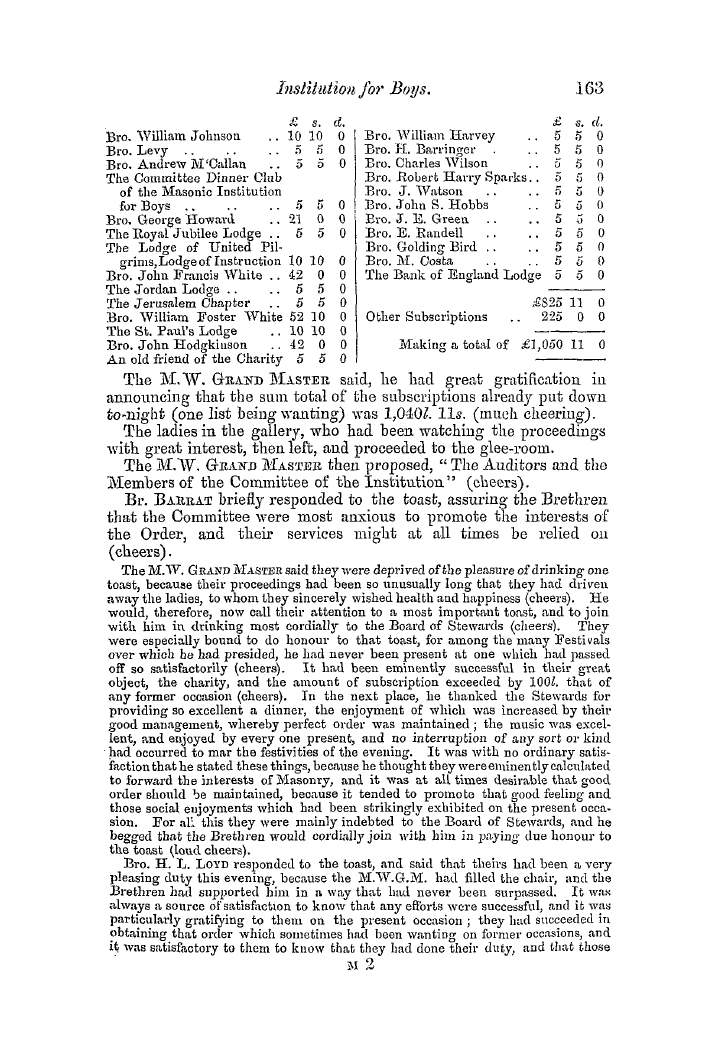

Article THE UNIVERSALITY OF SUPERSTITION. ← Page 2 of 20 →

Note: This text has been automatically extracted via Optical Character Recognition (OCR) software.

The Universality Of Superstition.

by relies of their physical existence , possess the most powerful interest ; both as making the singularity of their genius and tlieir influence ox'er the cotemporary world . The question of early superstition becomes one of religious sentiment . The necessity of attributing the works of creation , and of providence to a ruling poxver or powersand the natural

, principle of reverence , gaxe rise to idolatry—the result of the incapacity of an unenlightened race to appreciate anything beyond the material world . Hence , among the Egyptians , arose the Avorship of the sun and moon , the deities Osiris and Isis , with that of oxen of A'arious kinds , as exemplified in the golden calf raised up at the very foot of the sacred mountain

, by the strangely perverse race , xvho had derived their customs from the land of then * captiA'ity . Hence the adoration of the fertilising hill , and its indAveller the crocodile , both objects of the deepest reverence . Egypt was the parent clime of almost

every species of pagan superstition . Learning , too , was there ; but , agreeably to the experience of later days , scientific acquirement alone was unable to guard against delusion concerning the supernatural , nor to steer safely through an ocean of charms , omens , dream-prophesyings , days of good and ill promise , and the vagaries of magical art .

Later on Ave fincl the elegant and accomplished Greek no less superstitious than his forerunner . The Greeks , as well as Romans , placed unbounded faith in divination , and in the prophetic nature of comets—ancl , guided by poetic fancy , gave birth to the beautiful mythologies AA'hich are subject of admiration to the scholar . The distinctive featiu-es of the Greek

and Roman superstition became , however , obliterated upon the Gothic conquest . Subsequently to this epoch all the superstition of Western Europe , or nearly so , is traceable either to ancient pagan ceremonies , or to the more recent elements of Gothic or Scandinavian origin .

The Scandinavian mythology bears several points of correspondence Avith that of the classics . The Grecian Elysium is represented in the northern Walhalla . The inhabitants of the latter region Avere supposed to employ themselves in drinking mead and feasting on the wild boar , during the intervals of then * chief aA'ocation , that of ferocious combat—bravery being the hi

ghest attribute of a Scandinavian deity . Jupiter is found in Odin—both supreme and warlike beings . Odin appears to haA'e been a real person , mighty in arms , and deified after death ; but whose authentic and fabulous actions have been undistinguishably amalgamated . The Roman xvar-god , Mars , is reproduced in Thor , the god of thunder—armed Avith a

Note: This text has been automatically extracted via Optical Character Recognition (OCR) software.

The Universality Of Superstition.

by relies of their physical existence , possess the most powerful interest ; both as making the singularity of their genius and tlieir influence ox'er the cotemporary world . The question of early superstition becomes one of religious sentiment . The necessity of attributing the works of creation , and of providence to a ruling poxver or powersand the natural

, principle of reverence , gaxe rise to idolatry—the result of the incapacity of an unenlightened race to appreciate anything beyond the material world . Hence , among the Egyptians , arose the Avorship of the sun and moon , the deities Osiris and Isis , with that of oxen of A'arious kinds , as exemplified in the golden calf raised up at the very foot of the sacred mountain

, by the strangely perverse race , xvho had derived their customs from the land of then * captiA'ity . Hence the adoration of the fertilising hill , and its indAveller the crocodile , both objects of the deepest reverence . Egypt was the parent clime of almost

every species of pagan superstition . Learning , too , was there ; but , agreeably to the experience of later days , scientific acquirement alone was unable to guard against delusion concerning the supernatural , nor to steer safely through an ocean of charms , omens , dream-prophesyings , days of good and ill promise , and the vagaries of magical art .

Later on Ave fincl the elegant and accomplished Greek no less superstitious than his forerunner . The Greeks , as well as Romans , placed unbounded faith in divination , and in the prophetic nature of comets—ancl , guided by poetic fancy , gave birth to the beautiful mythologies AA'hich are subject of admiration to the scholar . The distinctive featiu-es of the Greek

and Roman superstition became , however , obliterated upon the Gothic conquest . Subsequently to this epoch all the superstition of Western Europe , or nearly so , is traceable either to ancient pagan ceremonies , or to the more recent elements of Gothic or Scandinavian origin .

The Scandinavian mythology bears several points of correspondence Avith that of the classics . The Grecian Elysium is represented in the northern Walhalla . The inhabitants of the latter region Avere supposed to employ themselves in drinking mead and feasting on the wild boar , during the intervals of then * chief aA'ocation , that of ferocious combat—bravery being the hi

ghest attribute of a Scandinavian deity . Jupiter is found in Odin—both supreme and warlike beings . Odin appears to haA'e been a real person , mighty in arms , and deified after death ; but whose authentic and fabulous actions have been undistinguishably amalgamated . The Roman xvar-god , Mars , is reproduced in Thor , the god of thunder—armed Avith a